What does a Sun Microsystems cofounder do with his spare time? Well, if you’re Scott McNealy, you spend some if it lending your expertise to promising tech vendors that are looking to break into the IT big leagues. One such company that he has taken a personal interest in is Hardcore Computer, which recently introduced a line of servers that use liquid submersion technology. HPCwire spoke with McNealy to get his take on the technology and to ask him why he thinks the company deserves the spotlight.

McNealy signed on as a non-paid advisor and consultant with Hardcore in January at the behest of longtime friend and former Stanford classmate Doug Burgum. Burgum’s venture firm, Kilbourne Group, has invested in Hardcore, a Rochester, Minnesota-based computer maker that specializes in high performance gear based on the company’s patented liquid submersion cooling technology.

“This is one of the few companies innovating on top of the Intel architecture — rather than just strapping a power supply on and porting Linux,” McNealy told HPCwire.

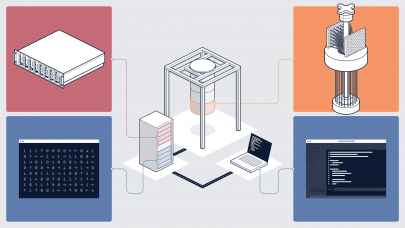

Hardcore makes a range of liquid-cooled offerings, including desktops, workstations, and servers. Its latest offering is the “Liquid Blade,” a server line the company announced in May 2010 and launched in November at the Supercomputing Conference in New Orleans (SC10). The new blade is more or less a standard dual-socket x86-based blade using Intel Xeon 5500 and 5600 Xeon parts. It sports eight DDR3 memory slots per CPU, six SATA slots for storage, and a PCIe x16 slot for a GPU card or other external device.

Hardcore makes a range of liquid-cooled offerings, including desktops, workstations, and servers. Its latest offering is the “Liquid Blade,” a server line the company announced in May 2010 and launched in November at the Supercomputing Conference in New Orleans (SC10). The new blade is more or less a standard dual-socket x86-based blade using Intel Xeon 5500 and 5600 Xeon parts. It sports eight DDR3 memory slots per CPU, six SATA slots for storage, and a PCIe x16 slot for a GPU card or other external device.

Liquid Blade’s secret sauce — and in this case it literally is a sauce — is Hardcore’s patented liquid submersion technology. The company uses a proprietary dielectric fluid, called Core Coolant, to entirely submerge the blades within a specially-built 5U rack-mounted chassis. The coolant is inert, biodegradable, and most importantly non-conductive, so all of the electrical components inside the server are protected.

As with any liquid coolant, the idea is to draw off the excess heat much more efficiently than an air-cooled setup and ensure all the server components are keep comfortably cool even under maximum load. According to the company literature, the Core Coolant has 1,350 times the cooling capacity of air. Since the coolant is so effective at heat dissipation and the internal fans have been dispensed with, the server components can be packed rather densely. In this case the 5U Hardcore chassis can house up to seven of the dual-socket blades.

The company launched its liquid-dipped server at SC10 last November to get the attention of the HPC community, but the offering is suitable for any installation where the datacenter is constrained by power and space. Besides HPC centers, these include DoD facilities, telco firms, and Internet service providers. “You have to look at the users who think at scale and have a huge electric bill,” explains McNealy.

The datacenter cooling problem is well-known, of course. As servers get packed with hotter and faster chips and datacenters scale up to meet growing demand, getting enough power and space has become increasingly challenging. Datacenter cooling has traditionally relied on air conditioning, but air makes for a poor heat exchange medium, and it’s hard to direct it where it’s most needed. “Air goes everywhere but where you want it to,” laughs McNealy. Cooling a hot server, he says is “like trying to blow a candle out from the other side of the room.”

Because of the density of the Hardcore solution, you need about 50 percent fewer racks to deliver the same compute. And since the blades essentially never overheat, one can expect better reliability and longevity. As any datacenter administrator knows, heat is a major cause of server mortality, especially in facilities filled to capacity.

But the really big savings is on the power side. Since cooling and the associated equipment take up such a large chunk of a datacenter energy budget, any effort to reduce these costs tends to pay for itself in just a few years. An independent study found that a Liquid Blade setup could reduce datacenter cooling costs by up to 80 percent and operating costs by up to 25 percent.

Hardcore isn’t alone in the liquid submersion biz. Other companies, most notably Austin-based Green Revolution, are providing these types of products. In the case of Green Revolution, they offer a general-purpose solution for all sorts of hardware — rack servers, blades, and network switches. The company will strip down the gear to its essentials and immerse the components in a specially-built 42U enclosure filled with an inert mineral oil.

But since Hardcore is dunking its own servers, it has the option to build high performance gear that would be impractical to run in an air-cooled environment. As McNealy points out, the efficient liquid cooling is a natural for the highest bin x86 chips running the fastest clocks. For example, the company could stuff Intel’s latest 4.4 GHz Xeon 5600 processors into its blades, and offer a special-purpose product for high frequency traders (as Appro has done, sans immersive liquid cooling, with its HF1 servers). Hardcore has never talked about such a setup for HFT, but it does tout the servers outfitted with high wattage graphics cards for GPGPU type computation. Applications using such capabilities include medical imaging, CGI rendering, engineering simulation and modeling and web-based gaming.

One the things McNealy has been working with the Hardcore people on is getting an apples-to-apples comparison of their liquid cooled gear versus conventional air-cooled servers. To do this, he says, you have come up with a higher level analysis that takes into account the service cost over the entire datacenter.

According to the company, the cost of a Liquid Blade setup is on par with a comparably equipped air-cooled product since all the fans are eliminated and the chassis design is simpler. If a user opted for Liquid Blade when it came time to upgrade their servers, they could start to realize energy costs savings immediately. But the big savings occur when a datacenter can be built from scratch with liquid submersion in mind.

In that case, the datacenter can dispense with a lot of the CRAC units, use 12-foot ceilings instead of 16-foot ones (no overhead air ductwork is needed), and use less UPS units thanks to reduced power requirements. The only extra cost comes with the chilled water to oil heat exchangers used to draw the heat from the chassis coolant. Also, since you can fit more servers into the same space, the datacenter floor space can be reduced by about 30 percent for a given compute capacity.

So why isn’t everyone flocking to liquid submersion? Customer inertia, says McNealy. According to him, he’s spent most of his career knowing the right thing to do and trying to get others to realize it themselves.

With Hardcore, the challenge is that most organizations are already set up with their existing air-cooled facilities, so a lot of the cost incentives for the big switch aren’t there. He thinks if a large Internet service provider bought into this technology for a new datacenter, the business could quickly take off. For McNealy’s Sun, that tipping point was in the late 80s when Computervision made a big deal to go with his company’s Unix-based workstations. Hardcore, no doubt would love to repeat history, this time with the likes of Google, Amazon, or Facebook.

“Their biggest challenges is the barrier to exit from the old strategy, not the barrier to entry to the new one,” says McNealy.