Just when it started to look as though the architectural course had been set for the next wave of large-scale supercomputers, today offered quite a shakeup to the standard.

And it’s not just the amount spent to turn a novel architecture into a pre-exascale reality, although to be fair, it’s rare indeed to see a lump $325 million deal from the Department of Energy to fund new systems with an extra $100 million added to support extreme scale technologies under the FastForward initiative.

Aside from the sheer investment figures, the fascinating part of what’s happening is architectural—and therefore, important in terms of what this means for how centers think about energy consumption, prioritization of extreme scale scientific and security challenges, and of perhaps to some degree, the slightly less dominant position of the U.S. in terms of its national supercomputing capability.

While many expected these first two of the new pre-exascale systems to come out of the CORAL collaboration between Oak Ridge, Lawrence Livermore, and Argonne national laboratories to follow the trends set by Titan and other accelerated Intel-powered x86 machines, those expectations were upended by IBM in today’s announcement about a new class of systems sporting GPUs via a close collaboration among OpenPower members IBM, NVIDIA and Mellanox.

Before we delve into an early overview of the systems, it’s worth noting that the very status of IBM’s role in the future of supercomputing had been called into question over the last year, making this a rather surprising announcement in its own right. From selling off their core HPC-oriented server business to Lenovo to quietly bringing the Blue Gene era to a close, it seemed that their interests were shifting toward a more general Power-based approach for all datacenters—not just HPC with its unique subsets of system choices.

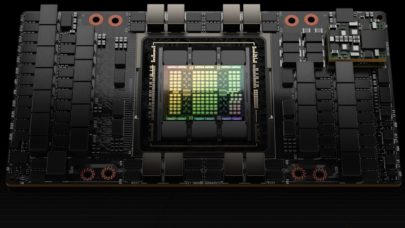

To be fair though, this is still what they’re doing. The massive procurement is for systems that are not exactly distinct HPC offerings per se, but rather more advanced and forward-looking variants on the overall OpenPower push to upend Intel’s dominance. However, with the addition of key technologies from Mellanox and NVIDIA, specifically the latter’s NVLINK technology, the new generation, which we heard for the first time today is called “Power9” IBM has found a way to maintain an edge at the high end while refining the Power approach to the wider datacenter market as these technologies mature and are put to the test at scale….and massive scale, at that.

The result of all of this are two systems that will be installed in the 2017 time frame. Summit, which will be housed at Oak Ridge National Laboratory and will be dedicated to large-scale scientific endeavors ranging from climate modeling to other open science initiatives. The other, called Sierra, is set to be installed at Lawrence Livermore with emphasis on security and weapons stockpile management.

Both are GPU-accelerated systems that have fewer nodes for all the performance they’re able to pack in due to the collaboration between NVIDIA and its Volta architecture, which for those who follow these generations, is two away from where we are now with Pascal expected in 2016. The key here is the NVLink interconnect, which is set to push new limits in terms of making these the “data centric” supercomputers IBM is espousing as the next step beyond supercomputers which have traditionally been valued according only to their floating point capabilities.

We will be exploring the technology in a companion piece that will immediately follow this one and offer a deeper sense of the projected architecture from chip to interconnect. However, to kick off this series, we wanted to provide a touchstone for these first inklings at what exascale-class systems might look like in the U.S. in the years to come.

One thing is for sure, these are packing a lot of punch in a far lessened amount of space. The Summit system at Oak Ridge is expected to push the 150 to 300 peak petaflop barrier, but according to Jeff Nichols, one of the most remarkable aspects of the system is how they were able to work partners IBM, NVIDIA, and Mellanox to create an architecture that can be boiled down to a much smaller number of nodes for far higher performance and a much larger shared memory footprint.

At this stage, Summit will be 5x or more the performance of Titan at 1/5 the size—weighing in at just around 3400 nodes.

“This shared memory capability and lower node count is important to our developers going forward,” he said. “I can say as a computational chemist myself that developers love having fewer nodes to manage and more shared memory per node to work with.”

The “data-centric” approach that IBM has been wrapping around for this announcement in particular is another key feature of the Summit system said Nichols. In addition to having the 5x to 10x performance boost using accelerators, which are already in play at Oak Ridge National Lab on the Titan machine, the capabilities for managing vast amounts of complex simulation data is critical. “We can ingest more data, more varieties of data, and explore modeling and simulation data in new ways that we couldn’t do even with Titan,” he explained. “As we move toward exascale, and this is certainly an early step towards that, we do feel that we have a good path forward in terms of how we’ll develop and deploy future systems along this architectural path” with both computational and data centric needs in mind.

As NVIDIA’s Sumit Gupta told us today that each of these nodes is so powerful that four of them alone today would make the Top 500. “You probably need a couple of racks of servers to get into the Top 500 but GPU performance will advance so much that we’ll get that with just four nodes. The central reason why the largest supercomputers are using accelerators is that CPU alone is too much power. A 150 petaflop system today would be half the power of Vegas—and that isn’t going to improve much.”

Gupta added that NVLink, which will explore in depth in a follow-up technical piece, is central because the CORAL collaborators wanted a fast processor but required a data movement paradigm that would allow data to be handled quickly without extra hops. The traditional CPU and GPU connected traditionally over PCIe has been great for classical high performance computing, he noted, but with high throughput computing users at that scale need the processors to be able to move data efficiently from point to point.

These features are key for the weapons stockpile program that is central to national security where the Sierra system will offer a massive increase in performance and efficiency at Lawrence Livermore. This machine is expected to offer in excess of 100 peak petaflop performance.

As LLNL’s Mike McCoy said today, “Simulation is critical to our stockpile program—it’s critical for us to make sure we never have to return to nuclear testing. But our 3D weapons simulations codes involve 3D applications, multiple physics packages, and our major codes easily run over a million lines not to mention the databases they employ. At the end of the day, key national security decisions are made based on these calculations but the question is always how do we know these systems are going to do the work we need?

In answering his own question he explained the way value of the partnership of OpenPower members. “This is not an off the shelf approach—the partnerships are strong and we share the risk in development and deliver platforms that can rapidly come into production and serve our needs. This effort is achieved through a systems integration approach and there will be tight integration between the vendors and code development teams which is called codesign—this has been interestingly enough applied into the past and led to advances like the Blue Gene L that led to advances and performed. This partnership represents a huge opportunity to deliver these and future first gen exascale systems.

We’ve displaced an Intel-based system at ORNL and we haven’t been there for a number of years. It’s a nice achievement for us,” said IBM’s Dave Turek in a conversation today. But the real value in this news is how it could represent the first seismic shift away from the FLOPS-centric approach to large-scale systems to one that takes the problems of data to heart at the core. “We are aided here not because of anything other than what we’re seeing in terms of the evolution of the marketplace through direct measurement how necessary it is to simultaneously deal with analytics in concert with modeling and simulation. If you look at an example like seismic processing and you go back ten years, the bulk of the time would have been dedicated to the algorithm and making it faster but what’s transformed the conversation is the radical influx of data. Now when you inspect the infrastructure that’s being deployed in examples like this, there’s a tremendous amount of mundane data sorting and managing that’s taking up the compute.

Just as efforts like this have bolstered IBM’s supercomputing products overtime, this new collaboration represents a shift for the company. IBM has in fact established an entirely new HPC roadmap—all around the concept of data centric computing. With these systems, the balance of performance, data movement, memory, and overall footprint are balanced with the needs of the new generations of highly scalable codes under development now with assistance from NVIDIA and IBM.

Follow up with us during your SC travels over the weekend and on Monday for more detail about the architectural features we’ve been able to tease out of a few conversations with IBM, NVIDIA, Mellanox and others.