During SC16, Exascale Computing Project Director Paul Messina hinted at an accelerated timeline for reaching exascale in the US and now we have official confirmation from Dr. Messina that the US is contracting its exascale timeline by one year.

Under the updated plan, the US will still be fielding at least two exascale machines in the next seven years. One of those machines remains on the original timeline – targeting delivery for 2022 and acceptance in 2023. However, the other machine is now on track for delivery in 2021 and acceptance in 2022. Further the intention of the DOE is that that first machine will employ a novel architecture.

The lifespan of the project has also changed from the original, 10-year timeline (2016-2025) to the current seven-year plan (mid-2016 through mid-2023). The original timeline provided three years after delivery of the (at least two) exascale systems for applications and software tuning; those activities will now begin during the final year of the project and will continue on after that, but not under the ECP.

As China, Japan and the EU have pushed ambitious exascale computing timelines, some have asked whether the United States was doing enough to maintain its competitive edge in an area so critical to national competitiveness. In 2002, when Japan grabbed a substantial lead on the TOP500 supercomputing list with the Earth Simulator, the US took that as a wake up call to reassert its dominance. Since 2013, China has claimed that vaunted number one spot, and there hasn’t been a similarly robust counter from the US. If the new exascale schedule is matched with the funding it needs to succeed, the US will be in a better position to advance its scientific, technical and military leadership.

“Of course having a seven year project instead of ten means something had to change,” said Messina. First of all, the contracted timeline will come at a cost, both dollar cost since doing things faster costs more money and power cost since that’s one less year to achieve the target power footprint of 20-30 MW.

Then there’s the impact on the activities of the project. “The applications teams, the codesign centers and the software technology efforts now have to get ready about a year earlier so that is a challenge but we believe we can meet it,” said Messina. “The novel architecture aspect means that we are trying to open things up so that some promising new ideas, or products – building blocks – are in play and we believe there are some options that can be put in place as an exascale system in that time frame – but the benefit to offsetting a year is that we don’t have two to deal with two systems simultaneously.”

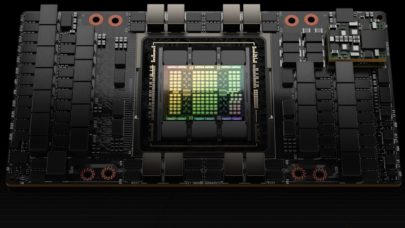

In this case novel architecture doesn’t mean quantum computing or something exotic like that. The DOE still wants something that can be credibly put together at very larger scale. The PathForward program, like Design Forward and Fast Forward before it, was created to develop the technology pipeline needed for extreme-scale computing.

“Some of the things that the vendors proposed in the PathForward project do have some novel ideas,” said Messina. “There are emerging processor architectures that seem quite promising – one would expect that there will be some fairly large systems with those processor architectures available within a couple years. There might be an accelerator that’s a different design for an accelerator than the ones that are prevalent today. There are also some new ideas for interconnects that we think would have benefits so that it could be a combination of things that would result in a novel architecture.”

The DOE received 14 PathForward proposals in July and evaluated them in August. Six proposals were selected. When the DOE issued the RFP, they requested that the vendors propose different work packages so that they could choose the ones that were most compelling. So while six vendors have passed evaluation, the DOE is not planning to fund every work package, just a subset of them.

Because of this mixing and matching of the various proposed work packages, the DOE is hammering out detailed statements of work with the respective vendors. The funding for the vendor contracts has already been approved and Messina says it’s likely that the DOE will be issuing signed contracts with the six vendors in January 2017.

The PathForward program will inform the designs of both ECP systems, but the DOE is anticipating initiating another similar RFP in the near future aimed at generating promising technology options specifically for the 2021 target system.

The takeaway here is that the United States will surely reach the next big 1,000X performance horizon but how fast that happens correlates to how much it is willing to invest. We won’t know for sure whether that funding commitment is there until the FY18 budget is announced.