Graphcore means business – and it should, given the paradigm shift it wants to provoke. The ambitious startup, which emerged from stealth in 2016, makes Intelligent Processing Units, or IPUs: massive processors specifically designed for AI computing, which Graphcore intends to be “the worldwide standard for machine intelligence compute.” In a marketplace crowded by CPUs and GPUs from AMD, Arm, Intel and Nvidia – and with users who increasingly rely on these systems for mission-critical functions – encouraging such a drastic shift can be a tall order. To that end, Graphcore is highlighting a use case at the University of Bristol, which tested IPUs against Nvidia GPUs, finding the IPUs to mostly outperform the GPUs while consuming less power – and, perhaps most crucially, without encountering substantial growing pains from the switch.

Racing to stay ahead of the LHC

At the University of Bristol, Jonas Rademacker (a professor of physics) and his colleagues are working on crunching data from the largest machine on the planet: the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in Switzerland. Specifically, they work with data from the LHCb experiment, which examines the decays of certain particles in order to provide insight into the aftermath of the Big Bang. The detector that serves the LHCb experiment produces around 20 TB of data per second when running, necessitating massive computing power to process and analyze – needs that will only grow as the experiment prepares for another major detector upgrade.

“It’s widely recognized in the particle physics world that we are running out of computing power,” Rademacker said in an interview with HPCwire. “At least if we do what we used to do – if we run on CPUs, and if we write the kind of code that we used to write.”

As Rademacker tells the story, one of the PhD students working on the LHCb data was also working for Graphcore. When the student started explaining the IPU to Rademacker and his colleagues, Rademacker recalls thinking: “Wow, this might be exactly the kind of thing that we have been looking for.”

Testing the IPU

Rademacker reached out to Graphcore, asking to test their IPUs for a proof-of-concept on particle physics workloads. Shortly thereafter, the researchers had Graphcore’s Dell EMC DSS8440 IPU server (the standard server product for first-gen IPUs) in-hand. Each DSS8440 server is equipped with eight Graphcore PCIe cards (each with two of its first-gen IPUs), along with Intel CPUs, a substantial amount of memory, and other basic server components. In total, a DSS8440 delivers 1.6 petaflops of mixed-precision compute power.

Within just a few months, the research team was running the DSS8440 through a barrage of particle physics tests: generative adversarial networks (GANs) for simulated particle track reconstruction; neural networks for particle identification; and Kalman filters, which particle physicists use to examine time series data from experiments and estimate hidden variables to describe the data.

Across all workloads, the IPU delivered. Comparing it to the Nvidia Tesla P100 GPU – which, according to the researchers, came in at a similar price point – the IPU-based system “significantly” outperformed the GPU when working with GANs at low batch sizes, delivering speedups between 3.9x and 5.4x. In particle identification tasks, the researchers again found that the IPU outperformed the P100 – this time, at all batch sizes. Furthermore, the IPU delivered these results while operating at half the power consumption of the P100.

Clearing a path for technology adoption

For Rademacker and his colleagues, this was a successful proof of concept. “Throughput per Swiss franc spent and, not independently of that, throughput per kilowatt-hour spent – these are the things we really care about,” Rademacker said.

Still, upgrades to particle physics-associated technology can be a lengthy process, owing to the high stakes of technical hangups with large projects like the LHC. “People are fairly conservative in this field,” Rademacker said. “There’s inertia that comes with existing technology, so moving is always hard.”

So the plan isn’t to put the LHC’s day-to-day data in the hands of Graphcore’s IPUs – yet. Next, the Bristol team will be scaling up its tests of the IPU, running experiments that resemble – and even parallel – real LHCb workloads. Despite the necessarily slow pace of testing a new piece of core technology, Rademacker stressed how Graphcore’s tech made this often-arduous process relatively easy.

“Increasingly in particle physics, people use GPUs,” he explained. “And that sort of happened because they got easier to use. It is this reason why it’s so important that it didn’t take long to program these and get used to them. In our field, PhD students have just over three years of time – they can’t take two years of time to learn a completely new programming language and then one year to program in it. … People have to be able to pick these things up quite quickly if you want them used in our field.”

Matt Fyles, SVP of software at Graphcore, agreed. “The most important thing is that he’s been able to take his workloads and his models that run on the Nvidia platform, move them across to Graphcore and get performance out of them,” Fyle said. “So from our point of view, what it is is a great validation that people can run lots of things on IPUs. We’re not having to handhold every single person who uses it through a process of very difficult user interaction.”

“It’s really a testament to the kind of maturity we’re starting to get into the software – these kinds of projects, which are real, they’re not just experimental things off to the side that people are playing around with. They’re real work and it’s great that they’re starting to bring those to the IPU,” he continued.

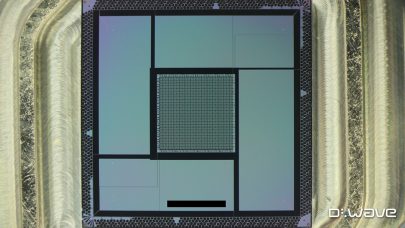

Finally, it should be noted that the particle physics research used Graphcore’s first-gen IPU products – and that Graphcore debuted its second-gen IPU platform, the IPU-Machine M2000, just last month. The M2000 uses Graphcore’s new Colossus Mk2 GC200 IPU processors, a 59.4 billion-transistor behemoth of a chip that Graphcore called “the most complex processor ever made.” While early delivery of the M2000 systems has already begun for some early customers, full production shipments aren’t slated to begin until Q4 of this year.