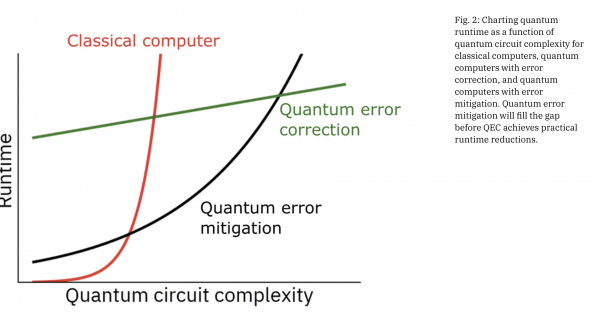

At IBM’s Quantum Summit last November, the company issued a detailed roadmap and declared it would deliver quantum advantage (better than classical computers) on selected applications in 2023. It was a bold claim that was greeted with enthusiasm in some quarters and skepticism in others. Today, IBM reiterated that claim with a lengthy blog on how error mitigation is the key to achieving quantum advantage (QA) while still using noisy intermediate scale quantum (NISQ) computers.

“There’s still a common refrain in the field if you want value from a quantum computer, it needs to be a large, fault tolerant quantum processor. Until then we’re stuck with noisy devices, inferior to classical counterparts,” an IBM spokesperson told HPCwire. “Our team has a different view. They have developed new techniques to draw ever more value from noisy qubits.”

The blog, written by Jay Gambetta, IBM fellow and vice president of quantum and HPCwire Person to Watch in 2022, and research colleagues Kristan Temme, Ewout van den Berg, and Abhinav Kandala argues that probabilistic error cancellation is the secret sauce, which when combined with other advances, will enable IBM to make good on its promise to deliver selective quantum advantage sometime next year. It’s an important part of IBM’s long-term path to fault-tolerant quantum computing.

The IBM researchers write:

“The history of classical computing is one of advances in transistor and chip technology yielding corresponding gains in information processing performance. Although quantum computers have seen tremendous improvements in their scale, quality and speed in recent years, such a gradual evolution seems to be missing from the narrative. Indeed, it is widely accepted that one must first build a large fault-tolerant quantum processor before any of the quantum algorithms with proven super-polynomial speed-up can be implemented. Building such a processor therefore is the central goal for our development.

“However, recent advances in techniques we refer to broadly as quantum error mitigation allow us to lay out a smoother path towards this goal. Along this path, advances in qubit coherence, gate fidelities, and speed immediately translate to measurable advantage in computation, akin to the steady progress historically observed with classical computers.

“Of course, the ultimate litmus test for practical quantum computing is to provide an advantage over classical approaches for a useful problem. Such an advantage can take many forms, the most prominent one being a substantial improvement of a quantum algorithm’s runtime over the best classical approaches. For this to be possible, the algorithm should have an efficient representation as quantum circuits, and there should be no classical algorithm that can simulate these quantum circuits efficiently. This can only be achieved for specific kinds of problems.”

That’s the IBM plan.

Many in the quantum community agree. Others demure. Photonic-based quantum computing start-up PsiQuantum has consistently said that pursuit of full fault-tolerance is the only realistic way to produce practical, broadly useful quantum computers. PsiQuantum has embarked just such a strategy. (See HPCwire article, PsiQuantum’s Path to 1 Million Qubits.)

Analyst Bob Sorensen, chief quantum analyst for Hyperion Research, noted that IBM’s portrayal of the quantum industry, or at least big portions of it, as clinging to the idea that achieving fault-tolerant quantum computing is necessary before achieving usefulness may have been overstated. “I think there’s a lot more optimism for error-tolerant NISQ systems than is being suggested,” noted Sorensen.

Nevertheless, he was impressed with IBM’s activities. “What IBM is doing, as a full stack company, is addressing error correction at every level, down to the qubit structure and all the way up to software. They can cover everything in between. That’s a key advantage for a full stack vendor. So I think IBM is trying to aggressively take advantage of its full stack perspective. [Moreover,] they’re not putting everything under the hood. They’re saying, here’s our error correction. Here’s how you guys can play in that game as well,” said Sorensen.

Sorensen said, “I was more struck by IBM’s emphasis on runtime improvement and how all of its efforts, not just error correction per se, are aimed at reducing runtime. They’re moving away from a somewhat more abstract, classical versus quantum argument, to an emphasis on how their runtime is improving on these applications. That’s something that every classical guy can resonate with. That emphasis on runtime was an interesting perspective, because it embodies all of the things that they’re looking at – circuit depth, error rates, and the algorithms themselves. And it’s a much more accessible version of in my mind of the quantum volume measure (benchmark measure).”

Sorensen thought the blog, ostensibly about error mitigation and achieving quantum advantage, was really a broader positioning statement. The lengthy IBM blog did encompass a mini-summary of its steady advances to date, along with a deeper description of its error mitigation efforts.

Looking at error mitigation, IBM has developed two general purpose methods: one called zero noise extrapolation (ZNE); and one called probabilistic error cancellation (PEC). “The ZNE method cancels subsequent orders of the noise affecting the expectation value of a noisy quantum circuit by extrapolating measurement outcomes at different noise strength,” write the authors. PEC, says IBM, can already enable noise-free estimators of quantum circuits on noisy quantum computers.

IBM issued a PEC paper in January, which noted, “Noise in pre-fault-tolerant quantum computers can result in biased estimates of physical observables. Accurate bias-free estimates can be obtained using probabilistic error cancellation (PEC), which is an error-mitigation technique that effectively inverts well-characterized noise channels. Learning correlated noise channels in large quantum circuits, however, has been a major challenge and has severely hampered experimental realizations. Our work presents a practical protocol for learning and inverting a sparse noise model that is able to capture correlated noise and scales to large quantum devices.”

IBM was able to demonstrate PEC on a superconducting quantum processor with crosstalk errors. Here’s a somewhat lengthy excerpt (to avoid garbling) from today’s blog digging into PEC:

“In PEC, we learn and effectively invert the noise of the circuit of interest for the computation of expectation values by averaging randomly sampled instances of noisy circuits. The noise inversion, however, leads to pre-factors in the measured expectation values that translate into a circuit sampling overhead. This overhead is exponential in the number of qubits n and circuit depth d. The base of this exponential, represented as γ̄, is a property of the experimentally learned noise model and its inversion. We can therefore conveniently express the circuit sampling overhead as a quantum runtime, J:

J = γ̄ nd β d

“Here, γ̄ is a powerful quality metric of quantum processors — in technical terms, γ̄ is a measure of the negativity of the quasi-probability distribution used to represent the inverse of the noise channel. Improvements in qubit coherence, gate fidelity and crosstalk will reflect in lower γ̄ values and consequently reduce the PEC runtime dramatically. Meanwhile, β is a measure of the time per circuit layer operation (see CLOPS), an important speed metric.

“The above expression therefore highlights why the path to quantum advantage will be one driven by improvements in the quality and speed of quantum systems as their scale grows to tackle increasingly complex circuits. In recent years, we have pushed the needle on all three fronts.”

Here’s IBM’s overall checklist of notable milestones:

- “We unveiled our 127-qubit Eagle processor, pushing the scale of these processors well beyond the boundaries of exact classical stimulability.

- “We also introduced a metric to quantify the speed of quantum systems — CLOPs — and demonstrated a 120x reduction in the runtime of a molecular simulation.

- “The coherence times of our transmon qubits exceeded 1 ms, an incredible milestone for superconducting qubit technology.

- “Since then, these improvements have extended to our largest processors, and our 65-qubit Hummingbird processors have seen a 2-3x improvement in coherence, which further enables higher fidelity gates.

- “In our latest Falcon r10 processor, IBM Prague, two-qubit gate errors dipped under 0.1%, yet another first for superconducting quantum technology, allowing this processor to demonstrate two steps in Quantum Volume of 256 and 512.”

The blog, while not at the depth of a technical paper, has a fuller discussion of the error mitigation schemes, and IBM presents a few examples of error-corrected circuits run on its processors versus classical.

IBM points out that while the improvements in γ̄ might seem modest, the run-time implications (exponential) of these γ̄ improvements are huge — for instance, for a 100-qubit circuit of depth 100, the runtime overhead going from the quality of Hummingbird r2 (version of processor) to Falcon r10 is dramatically reduced by 110 orders of magnitude.

IBM presents a second example of how reductions in two-qubit gate errors will lead to dramatic improvements in quantum runtime. “Consider the example of 100 qubit Trotter-type circuits of varying depth representing the evolution of an Ising spin chain. This is at a size well beyond exact classical simulation. In the figure below we estimate the PEC circuit overhead as a function of two-qubit gate error.

“As discussed above, two-qubit gate errors on our processors have recently dipped below 1e-3. This suggests that if we could further reduce our gate error down to ~ 2-3e-4, we could have access to noise-free observables of 100 qubit, depth 400 circuits in less than a day of runtime. Furthermore, this runtime will be reduced even further as we simultaneously improve the speed of our quantum systems.”

The IBM team write, “We can therefore think of our proposed path to practical quantum computing as a game of exponentials. Despite the exponential cost of PEC, this framework, and the mathematical guarantees on the accuracy of error mitigated expectation values, allow us to lay down a concrete path and a metric (γ̄) to quantify when even noisy processors can achieve computational advantage over classical machines. The metrics γ̄ and β provide numerical criteria for when the runtime of quantum circuits will outperform classical methods that produce accurate expectation values, even before the advent of fault tolerant quantum computation.

“To understand this better, let us consider the example of a specific circuit family: hardware-efficient circuits with layers of Clifford entangling gates and arbitrary single-qubit gates. These circuits are extremely relevant for a host of applications ranging from chemistry to machine learning. The table below compares the runtime scaling of PEC with the runtime scaling of the best classical circuit simulation methods, and estimates the γ̄ required for error mitigated quantum computation to be competitive with best-known classical techniques.”

The blog is best read directly and provides a better view of what IBM sees as its path to quantum advantage using error mitigation techniques. So far, IBM has generally hit its milestones (hardware and software). The latest roadmap includes delivery of previously announced single-chip 433-qubit Osprey processor this year and 1,121-qubit Condor processor next year, but introduces newly architected processors intended for use in multi-chip modules, starting with a 133-qubit (Heron) processor in 2023, a 408-qubit processor (Crossbill) and 462-qubit processor (Flamingo) in 2024, and leading to the 1386-qubit processor (multiple chips) Kookaburra in 2025.

The blog’s concluding statement was quite broad:

“At IBM Quantum, we plan to continue developing our hardware and software with this path in mind. As we improve the scale, quality, and speed of our systems, we expect to see decreases in γ̄ and β resulting in improvements in quantum runtime for circuits of interest.

“At the same time, together with our partners and the growing quantum community, we will continue expanding the list of problems that we can map to quantum circuits and develop better ways of comparing quantum circuit approaches to traditional classical methods to determine if a problem can demonstrate quantum advantage. We fully expect that this continuous path that we have outlined will bring us practical quantum computing.”

Link to IBM blog, https://research.ibm.com/blog/gammabar-for-quantum-advantage