Update: The CHIPS and Science Act was signed into law on Aug. 9, 2022.

After two-plus years of contentious debate, several different names, and final passage by the House (243-187) and Senate (64-33) last week, the CHIPS and Science Act will soon become law. Besides the $54.2 billion provided to boost US-based chip manufacturing, the act reshapes US science policy in meaningful ways. NSF’s proposed budget is increased and a new Directorate for Technology, Innovation, and Partnership (TIP) is added. NIST’s profile and funding gets big boosts. DOE’s Office of Science office also fared well.

The final bill blends core science provisions of the America COMPETES Act of 2022 (House) with the Senate’s 2021 US Innovation and Competition Act (USICA). Fully parsing the bill’s 1,000-plus pages of provisions will take time. While most of the recent attention has focused on the $54.2B provided for chipmaking, the bill actually calls for about $280 billion in spending. The caveat is the bulk of the spending has only been authorized and must subsequently be appropriated by congress.

It’s been a long path forward for the legislation, which got its start in 2020 as the Endless Frontier Act, an ambitious proposal by Senators Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and Todd Young (R-IN) to dramatically expand NSF (see HPCwire coverage, $100B Plan Submitted for Massive Remake and Expansion of NSF). Inevitably, the supply-chain shortages caused by the pandemic, emerging geopolitical tensions, and recent cyber-security concerns injected a wider compass of elements into the legislation as it moved through Congress.

Physics Today has excellent recap of the final bill and its re-shaping process. Here’s brief excerpt of non-chip funding highlights from that article:

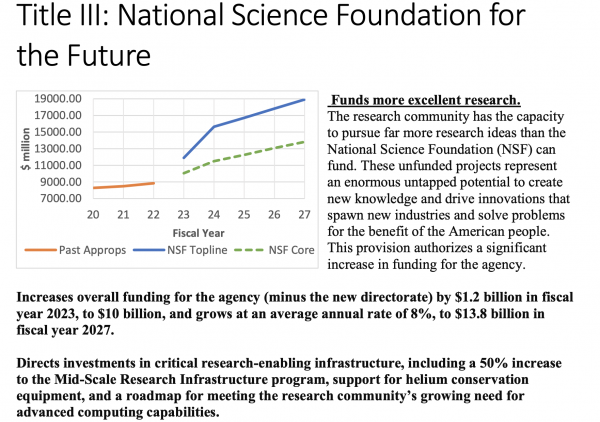

“[The bill] recommends that over the next five years Congress should roughly double the annual budgets of NSF and NIST, to $18.9 billion and $2.3 billion, respectively, and increase funding for the DOE Office of Science by nearly 50%, to $10.8 billion. It also proposes that parts of DOE beyond the Office of Science receive $4 billion to upgrade infrastructure at national labs and $11.2 billion for work on the same key technology areas supported by the TIP directorate.

“Those figures mostly represent a blend of proposals offered in the House and Senate bills. One exception is that the bill entirely drops a USICA provision that recommended an immediate doubling of the budget of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. It also omits budget targets for NASA but still provides policy direction for the agency.

“In contrast to the semiconductor funds in the bill, the agency figures are only authorizations, meaning Congress is not obligated to provide the money and will decide whether to meet the targets on a year-by-year basis. Congressional appropriations often fall well short of authorized levels, as occurred with those set by the America COMPETES Acts of 2007 and 2010, which also proposed ramping up the budgets of NSF, DOE, and NIST.”

Bloomberg ran an interesting, positive-but-cautionary editorial that reflects a chorus of opinion. The dust has clearly not yet settled for this bill. There are winners and losers and there will be lot to track moving forward. (see overall summary and NSF drill down below taken from different congressional documents)

The HPC community, perhaps not surprisingly, has been generally supportive of the bill. The devil will be in the details.

Rick Stevens, associate laboratory director, Argonne National Laboratory, said, “I think in general getting growth in the authorization is helpful, I would like to see the physical science budgets on a 10-year doubling trajectory and this helps with that.

“The specifics of course matter as DOE’s facility strategy and research priorities are being refined and updated frequently. As a general statement, we want to see progress on: building out the exascale facilities ecosystem at the labs, continuing support for software and applications for exascale, rebuilding the base research math and CS programs that were used to bootstrap exascale, starting new facilities investments for edge computing with the DOE experimental facilities and of course the investments needed to drive progress on the AI for Science and National Security initiatives. All of this will build on the exascale foundation and the planning for the next generations of computing that is happening now.

“The ongoing task over the next few years is to turn the good will encoded in the authorization language into the specific resources the programs need,” said Stevens

Alex Larzelere, long-time government policy-watcher and former federal director for the DOE Office of Nuclear Energy’s Modeling and Simulation Energy Innovation Hub, noted, “Even if it was an appropriation, it will likely take a long time (a year or so) to get the money out the door. DOE Office of Science and the NSF are required to use a “peer review” process to fund projects. That starts with a workshop, which leads to developing a “call” for proposals, then proposers have some time to prepare their response, then the responses are peer reviewed, the results of which are then used by the feds to make grant decisions. At that point, the grants have to be negotiated and finally awarded, which really is an authorization to incur expenses. Those then turn into invoices that are submitted, and after all that, actual money is paid out by the government. A long process.”

So it begins, or at least it will begin as soon as President Biden signs the bill, which is expected to be soon.

On balance, applied technology, science security, and workforce readiness gain more emphasis if not equal footing with basic research in the bill. The new TIP NSF Directorate has been directed to work on not more than five “societal, national, and geostrategic challenges” and not more than ten key technology areas. The latter are familiar: artificial intelligence, robotics, materials science and manufacturing, high performance computing, telecommunications, data management, quantum science and technology, biotechnology, energy technology, and “natural and anthropogenic disaster prevention or mitigation.”

Here’s a snapshot of broad DOE highlights excerpted from a summary prepared by Congress. It’s necessary to dig deeper into the bill itself for more detail:

- Authorizes $8.9 billion for FY 2023, rising to $10.9 billion in FY27 for the Office of Science. This is compared to $7.5 billion enacted in FY22.

- Provides a 6% annual increase for each of the Office’s core research programs.

- Ensures Office of Science construction projects and upgrades of major scientific user

- facilities have the resources they need to be completed on time and on budget, while incorporating COVID-19 related impacts.

- Authorization levels for construction activities and total program funding ensure that support for core research is able to grow annually, independent of each project schedule.

- Invests in the fight against climate change. Through its support of research to advance the next generation of energy storage, solar, hydrogen, critical materials, fusion energy, manufacturing, carbon removal, and bioenergy technologies, among many other areas, the Office of Science is uniquely positioned to help us reach our shared goals of developing energy that is clean, sustainable, reliable, and affordable.

NIST’s growing importance was also highlighted in the bill. Overall funding for the agency will increase by 40 percent to $1.5 billion in fiscal year 2023, with smaller but steady growth thereafter to $2.3 billion in fiscal year 2027. “This funding would help advance important research and support standards development for industries of the future, including quantum information science, artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, privacy, engineering biology, advanced communications technologies, semiconductors, and much more,” according to House summary documents.

EPSCoR (Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research) also received a boost. The new bill starts the NSF set-asides for EPSCoR at 15% of its funding increasing it to 20% over seven years. “The bill establishes an analogous set-aside for the DOE Office of Science, mandating at least 10% of the R&D funds it distributes to universities each year go to institutions in EPSCoR jurisdictions, a narrower requirement than proposed in USICA,” according to the Physics Today article.

As you can see, combing through the bill’s many provisions is daunting and there’s no easy-to-access compendium of tables or charts. Translating its provisions into programs will likewise be daunting. The House has provided a fact sheet sheet for the bill covering major provisions. Below are links to summaries of various sections also provided by the House. Good hunting.

REVITALIZING AMERICAN SCIENCE AND INNOVATION FOR THE 21ST CENTURY (House Fact Sheet)

“At the very core of the CHIPS and Science Act is the goal to revitalize American science and innovation for the 21st century. It is time for us to renew and strengthen federal support for the kinds of research and development initiatives that have long made the U.S. a beacon of excellence in science and innovation.

“The CHIPS and Science Act is ushering in a bold and prosperous future for our nation by ensuring we are able to compete globally and remain global leaders in science. Every section of the bill has a key role to play in achieving that goal. Learn more by viewing the fact sheets below.”

Title I: Department of Energy Science for the Future

Title II: National Institute of Standards and Technology For The Future

Title III: National Science Foundation for the Future

Title III: Bioeconomy Research and Development

Title V: Broadening Participation in Science

Title VI: Miscellaneous Science and Technology Provisions

Title VII: National Aeronautics and Space Administration Authorization Act

Related coverage: US CHIPS Act Close to Being Signed into Law