When the EuroHPC Summit was held last week in Gothenburg, there was a distinct shift in tone for the maturing supercomputing play. With LUMI and Leonardo – plus four other petascale systems – already operational, the question is no longer how to launch supercomputing infrastructure, but rather how to evolve and operate it. Workloads are an enormous part of that new question, with trials and benchmarks making way for the work that will justify the existence of machines that sometimes cost hundreds of millions to procure and operate. At the EuroHPC Summit and at Nvidia’s concurrent GTC event, one particular use case seems poised to serve as the flagship workload for EuroHPC’s flagship systems: Destination Earth, or “DestinE.”

Background

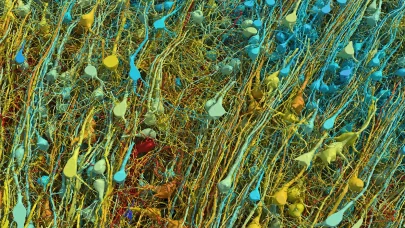

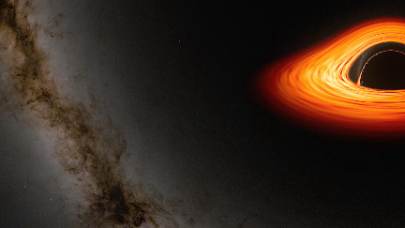

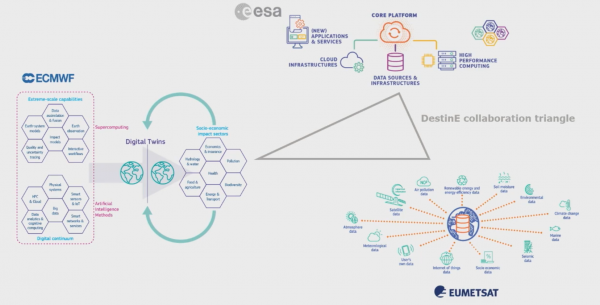

We covered DestinE in some detail back in October. The initiative will launch multiple digital twins of the planet, beginning with two – one for climate change adaptation, one for extreme natural disasters – with the aim of expanding to other critical issue areas (e.g. oceans, biodiversity) over time to create a “comprehensive digital twin of the Earth.” The digital twins will be supported by a data lake.

DestinE is led by the European Commission and, for now, is powered by core strategic partnerships with the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasting (ECMWF), the European Space Agency (ESA) and the European Meteorological Satellite Agency (EUMETSAT). EuroHPC, of course, is also a big player, providing much of the computational firepower for DestinE.

ECMWF is heading up the extreme weather digital twin (and the underlying “Digital Twin Engine”). Under that umbrella, ECMWF is delivering the global continuous component (continuously predicting extreme weather a few days in advance around the world) and Météo-France (and partners) are delivering the on-demand component (short-range, high-resolution predictions for Europe). Meanwhile, Finnish supercomputing center CSC and partners are working with ECMWF on the adaptation digital twin (climate simulations at multidecadal timescales). CSC is also, we recently learned, hosting the data lake, which is headed up by EUMETSAT. ESA, meanwhile, is providing the core service platform that will serve as a “user-friendly entry point for DestinE users.”

Peter Bauer, director for Destination Earth at ECMWF, spoke at both the EuroHPC Summit and GTC, and DestinE was a frequent point of reference for other speakers at the European event. Here are some of the things we learned.

Timeline

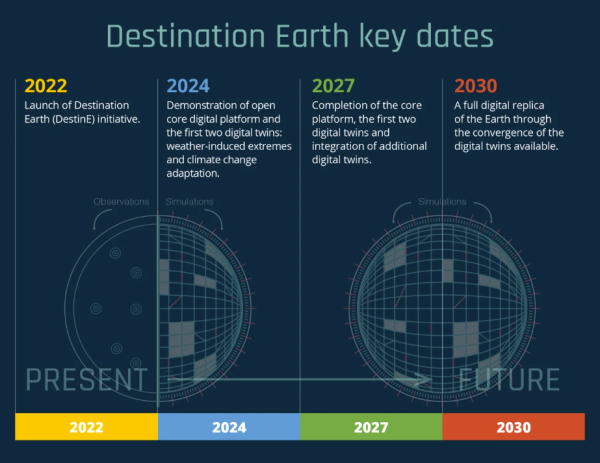

Bauer described DestinE, which launched “a year and a bit ago,” as a 7-to-10 year program. ECMWF has a contract for the first “implementation phase” of DestinE, which started in December 2021 and continues through June 2024. That period has a funding of €150M (~$163M). After that point, it’s expected to continue with a second phase that starts in the back half of 2024. That timeline lines up with what we heard previously: that the first two digital twins are slated for demonstration in 2024 and completion in 2027.

Allocations

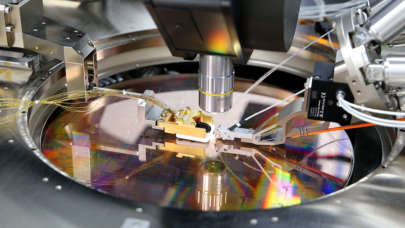

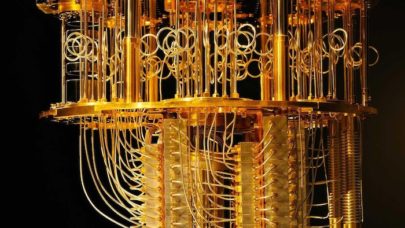

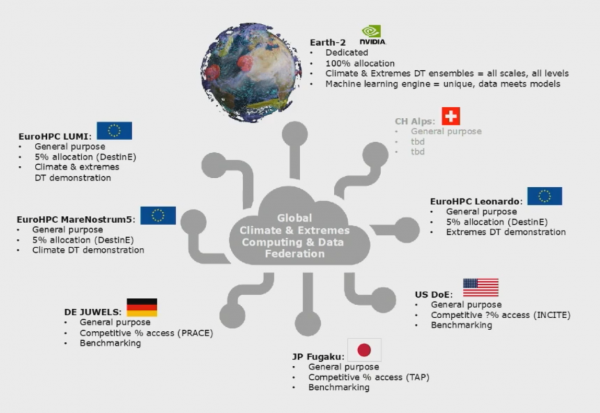

One of the most interesting things discussed in the talks is the specific EuroHPC allocation that has been awarded to Destination Earth. EuroHPC Executive Director Anders Jensen said in one of his talks that DestinE has been granted “special access,” pulling from a 10% time carve-out on EuroHPC computers reserved for “strategic European Union initiatives considered to be essential for the public good, or in emergency and crisis management situations.”

So far, DestinE is the first and only approved special access project. Through that special access, the program will receive access to four systems: all three pre-exascale systems – LUMI, Leonardo and (currently being installed) MareNostrum 5, as well as the petascale MeluXina system. DestinE will have dedicated access to 5% of the compute time on the pre-exascale systems, and it will also be able to use the remaining 5% allotted for special access until or unless that time is needed by another special access project. Those allocations are good until the end of 2024, but if DestinE fails to use the allotted time, the allocation could be adjusted downward.

“5% on each machine – and hopefully more on the exascale machines – it is something to start with,” Bauer said.

Expansion

That line about “hopefully more on the exascale machines” is telling, with Bauer saying that they can always “dream of more.” Said Bauer: “European collaboration is necessary, but not sufficient, in my view.”

To that end, Bauer talked about the possibilities for expansion outside the boundaries of the European Union. “There will be international links between the European efforts under Destination Earth and other, international efforts,” he said. “Right now, we are only starting that.” Included in this are private players like Nvidia (Bauer, of course, speaking at GTC); Nvidia has its own Earth digital twin in the works, Earth-2, which earned a mention and a spot on a speculative slide from Bauer. (That said, we didn’t hear much about Earth-2 from Nvidia this GTC.)

Also on that speculative slide: a grayed-out reference to Alps, the increasingly high-profile next-generation system at the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre (CSCS). Alps, which will be the debut of Nvidia’s Grace Hopper Superchips, was the subject of a separate talk by Thomas Schulthess, CSCS director. In that talk, Schulthess made substantial references to weather and climate as a “lighthouse use case” for Alps; while Schulthess stopped short of confirming Alps’ participation in Destination Earth, such a partnership seems likely, with Bauer referring to a “Swiss component” of DestinE.

Approach

In explaining Destination Earth’s raison d’être, Bauer explained the “waterfall” nature of how climate information is disseminated to policymakers and stakeholders. Through a “very established sequence of things that need to happen” for information to reach those people, he explained, scientists conduct original research, which then trickles down (the “waterfall” in question) through various sieves until it eventually reaches the “users” of that research.

“You see that in this logic, the user only comes in at the end,” Bauer said. “That’s an issue … If you were user-centric, you would almost turn this logic … upside-down.” If a politician wanted an answer to a question (in his example, estimates of coastal flooding in the Netherlands in 2030 and cost-effect adaptation scenarios for that flooding), Bauer said, they “would not be very well-served” by the current flow of information. “What you would probably want is a hierarchy of access levels, or abstraction levels, of the information, with full traceability across.”

Key to all of this: interactivity, particularly for non-expert users. “Our interpretation of what [digital twin] means is based on the marriage between enhanced quality and interactivity,” Bauer said. He even tied his talk into generative AI – the hot topic for this GTC – by prompting ChatGPT with his same question about flooding in the Netherlands and talking about how similar interactivity and clarity benefited end users.

Bauer stressed that while Destination Earth is a high-profile workload for EuroHPC, it wasn’t about using HPC for its own sake, but rather as a necessary tool for a critical issue. His talk was formally titled “Destination Earth and digital twins: A European opportunity for HPC,” but Bauer at one point proposed a different title that he considered more accurate to his vision, if a little less concise: “Destination Earth: An opportunity for creating a new type of information system in support of a sustainable future.”